Isolating Extremism

Mainstream Muslim sectarianism causes extremism. That is to say, factionalism among Muslim groups creates or cultivates pressures on individuals that lead them to choose extremist paths. Sectarian attitudes to mosque security close off any chance of restoring individuals to a safe environment. Belief that the threat has gone away just because it appears to have been shut out, makes mosque management complacent about working effectively against extremism with the authorities.

This document is part of a lengthy piece of work by Mehmood Naqshbandi, that is still to be completed and is very much in draft form. Comments would be extremely welcome, via the Contacts link above. Meanwhile, please tolerate missing references and faulty cross-references and return to the site for updates.

1. Summary

Security in a voluntary association

Only local, organic solutions will work

Empirical analysis and anecdotal sources

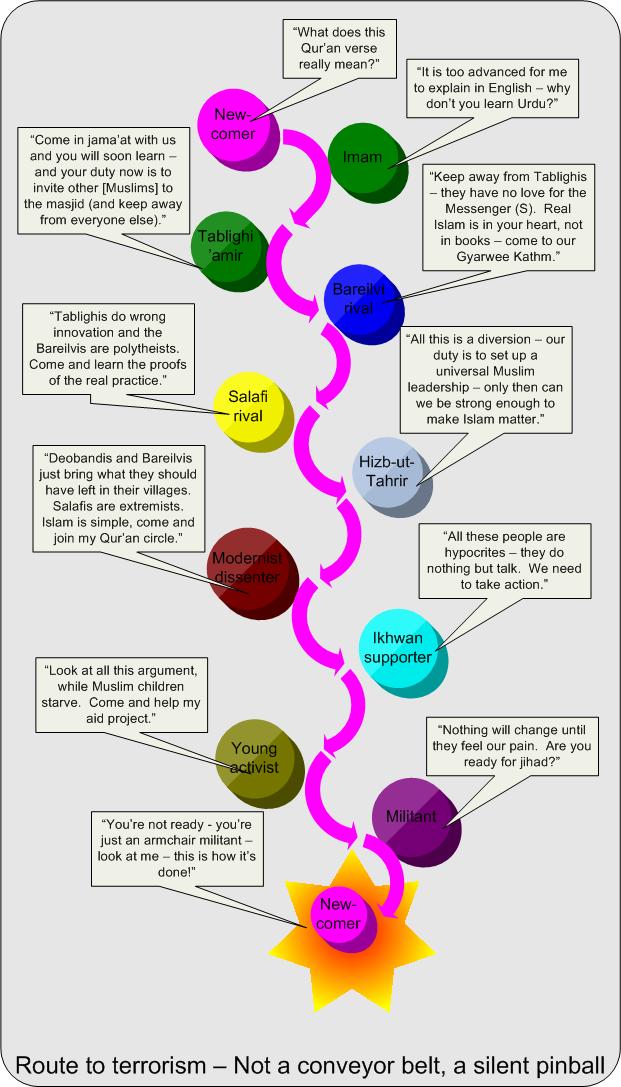

2. The Process – Rivalry over Neophytes

2.1 Neophytes and Masjid Sects

2.3 What the neophyte did next

2.4 How the Masjid management managed

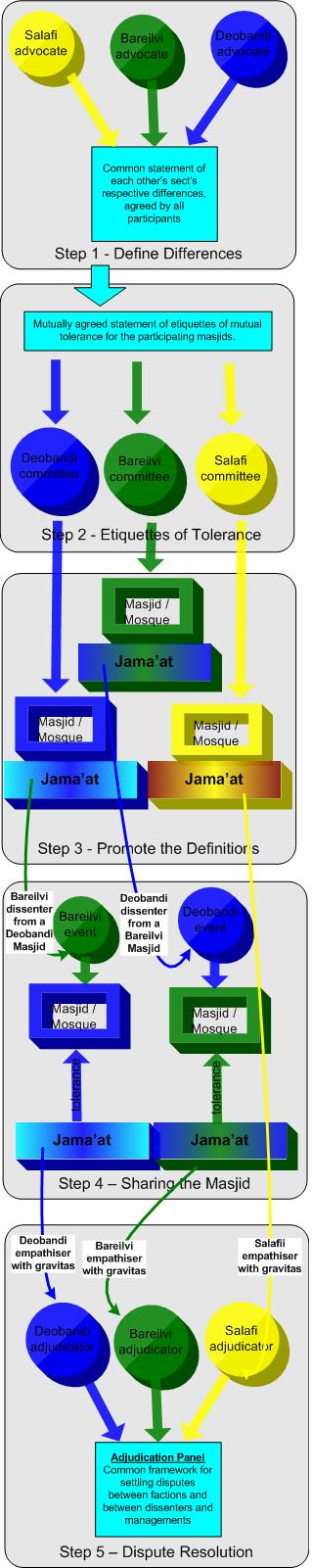

3. Recipe for Isolating Extremism

3.1 Undoing Sectarianism

Step 2 Etiquettes of Tolerance

Step 3 Publish and Promote the Definitions

3.2 Securing the Masjid

Step 6 Recognising the Problems

Step 7 Constitutional Stability

3.3 Safe Paths for Neophytes and Dissenters

Step 9 Give local figures knowledge of issues and factions

Step 10 Meet the needs of neophytes - impartially

Step 11 Move from factional tolerance to mutuality

1. Summary

Systemic Factionalism

Mainstream Muslim sectarianism causes extremism. That is to say, factionalism among Muslim groups creates or cultivates pressures on individuals that lead them to choose extremist paths. The process is straightforward – newly ardent Muslims, neophytes, are drawn into various factions that exist in and around every mosque. Unlike Christian denominational churches, mosques are used by Muslims from any faction or no faction. But mosque management is nearly always a clique of supporters of one of the older-generation sects. Mosque users may concur with management or may try to promote their own factional interest, be it a rival older-generation faction or an upstart new one. Open debate is banned in the mosque because it challenges the invariably weakly-founded authority of imams and mosque management and would thus open the way for a rival sect to take over. Factionalists therefore have to put their respective cases to the neophyte discreetly, out of sight, preferably by drawing him into an activity outside of the mosque altogether, to avoid drawing attention of rivals while the neophyte is still undecided. Or they may use the cover of normal, voluntary aid to the neophyte, e.g. sports, Arabic lessons or guidance for new Muslims, to make their case, again away from the mosque. Some of these factions might support militancy of some kind, most do not. But in competing for the attention of the newcomer, to show themselves to be the most committed, some individuals will proclaim support for militant action. Of those, some will then go on to involve themselves in it; for others, it is merely a display of bravado which the newcomer will see through. But then he himself may react against the empty bravado to go on to be involved in militant acts himself.

The critical problem is that sectarianism, combined with weak controlling structures, forces all factions, militant or civil, liberal, radical or conservative, to work in this covert way. Sinister recruitment cannot be distinguished from normal behaviour, so nobody in authority sees any danger signs until it is too late. Hence while mosques vigorously and honestly reject charges that they promote extremism, mainstream Muslim sectarianism unwittingly causes extremism. And incidentally, those who advise in favour of stronger controlling structures in or over mosques, would cause the mosques to become more rigidly denominational and close down any debate, driving all debate, moderate or militant, underground.

The process itself is nothing new or especially remarkable, though the outcome, in the current context, is unprecedented. Similar rivalry dynamics have been recognised for example among rival groups of soccer hooligans “supporting” the same team. And normal religious belief and zealotry are invariably associated with factionalism, and can often include extreme viewpoints; the same is true in pressure-group politics in democratic systems. For the most part these rarely involve acts of murder, though sometimes they certainly do. But among militant Muslims there are ample, well documented sources of material to inspire them to go on to murder – after having gone through the process described herein. ‘After’, because such materials are not the cause nor are they the process, since most of the same sources are available to everyone else, Muslim and non-Muslim, without having the same effect.[1]

Security in a voluntary association

Mainstream Muslim sectarianism may cause extremism to flourish, but the mainstream does not cause it intentionally or wittingly: it is not blameworthy; it causes extremism to flourish by shutting it out and driving it underground, unchecked and unseen. The mainstream does so, ironically, to protect itself from extremist influence. Shutting unwanted factions out is the only security measure that mosques have.

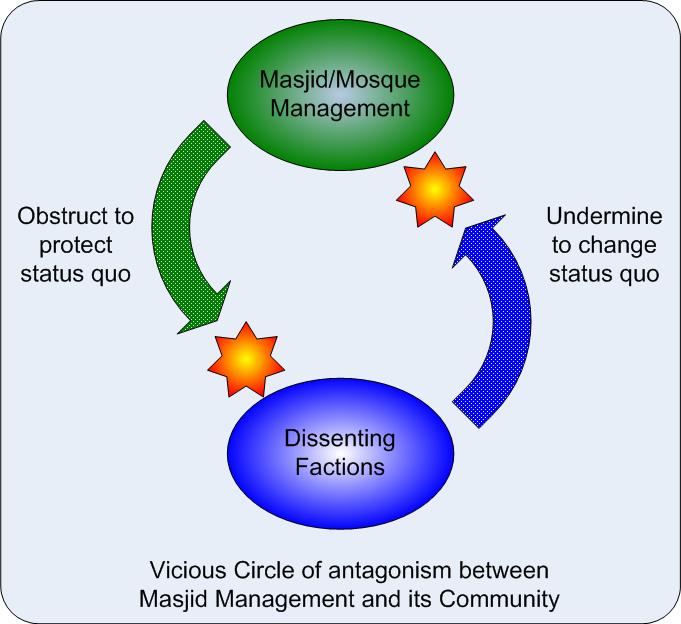

Shutting unwanted factions out is the only security measure that mosques have: Carping from the back rows and subverting newcomers is the only influence that dissenters have.

A better, more inclusive security model has to be found, one which allows credible, vigorous debate in an environment of mutual respect so that anyone involved will be aware of the full range of issues, arguments and implications. That way, extremist recruiters will no longer be able to monopolise the argument when they target a neophyte, and the cornered neophyte will know that he is able to defer the confrontation with the would-be recruiter and resume it in a forum where the arguments can be exercised properly. (Of course the malfeasant recruiter would not participate – and would thus reveal his intentions; and if the neophyte accepts the recruiter at face value, knowing he can debate the issues elsewhere, he is wittingly agreeing to his own recruitment.)

Countering sectarianism is vital to marginalise extremists, is in no way simple, and has to be successful – the wrong approach will have the opposite effect. Countering sectarianism has nothing to do with the fourteen-centuries’-old chestnut of Muslim unity; it has to do with tolerance, mutual respect, honesty and informed discussion between Muslim factions. These are values that Muslims seek in engagement with the rest of society, so it is both apt that we should seek them here and significant that they are hard to find between Muslims in Britain today.

Only local, organic solutions will work

I elaborate in this essay numerous friction points between factions, and I also try to describe a process by which sectarianism may be diminished. The process I describe is an organic, local process – it cannot be achieved from above, whether from major sects or from umbrella groups or by government-led social engineering. The process involves agreeing mutually acceptable definitions of the factions, agreeing initially very limited co-operation in religious/social ‘space’, and agreeing mutually acceptable protection of incumbent interests. (The people who are currently kept secure through exclusivity and sectarianism nevertheless are usually the primary benefactors of the mosques and Muslim organisations affected. They have a legitimate interest in protecting their investment.) Concurrently, those involved need their capacity built: they need to be coached in negotiation and arbitration skills; they will be drawn from among the least entrenched of the partisans and will need to be able to bring others along with them. Furthermore they need to take the process on to other neighbourhoods. The participants will need education – few adherents of one sect know much positive about their rivals; few know much about extremism, militancy, jihad, pluralism, pressure-group politics, or the multiple Islamic positions on all of these. And lastly the participants need to be reminded regularly of the goal, as I should remind the reader now: By diminishing sectarianism between the mosques it becomes possible to bring discussion and debate of Muslim issues, factional and sectarian issues, political issues, in from the shadowy margins. That has three outcomes.

- Firstly ordinary, politicised Muslims become free to debate the issues fully and openly, leading to normalisation of debate and better understanding of their multiple facets – it undermines simplistic, ‘single narrative’ ideas of extremist ideologies among ordinary Muslims.

- Secondly, it puts those with militant views but no past militant record, into the community spotlight – there is nothing intrinsically ‘wrong’ with their views, and having expressed them in a public place it becomes much harder for the same individuals to pursue them surreptitiously.

- Thirdly, with inter-factional debate taking place respectfully, in the open, there is far less need for discreet cajoling, unverifiable briefing and counter-briefing in the margins – so what does take place in the margins is far more likely to be a cause for concern, more likely to be a coven of militant plotters.

At the moment, intense sectarianism makes unverifiable briefing and counter-briefing in the margins utterly normal.

Policy implications

This analysis has strong implications for policy and practice in Britain. It is essential to permit open and fully informed discussion, among Muslims, of radicalism (almost always benign, positive and engaged) and extremism (almost always negative, but often surprisingly well engaged), and this is currently not possible in mosques and is actively discouraged by government and mass media. Yet to do so will challenge and so weaken the current, inadequate forms of mosque management. So it is vital that (i) mosque and Muslim organisations’ structures are made more secure, stable and capable; and simultaneously (ii) factional rivalries are subdued by demanding honesty, mutual respect and mutual co-operation between the factions.

The analysis does not translate well to other Western countries because the circumstances of Muslims in Britain are quite unique. Indeed this analysis demonstrates that policies that have been applied elsewhere in Europe are highly likely to fail in Britain, e.g. those which place centralised controls on mosques and imams, among many others.

Women

This paper throughout refers to the male circumstances. Practicalities for women are different – there are strands in both mainstream and radical versions of Islam that consider that discouraging the use of the mosque by women is authentic traditional practice, so, very often, women make other arrangements to meet. However similar sectarian pressures exist between groups of women meeting as between men meeting, and women include just as many outspoken radicals as men. Furthermore, practically all UK mosques with “radical” inclinations also cater extensively for women, unlike the conservative mainstream. (These same mosques - I have in mind Salafi-inclined mosques and those that cater predominantly for the Arab community - also cater extensively for English language and for converts, male and female, again unlike the mainstream. And “radical” certainly does not equate with “militant”, though many militants could be described as radical.)

Empirical analysis and anecdotal sources

This analysis is rooted in the practical experiences of its author, himself a convert since 1982, who has spent weeks or months at a time in scores of local Muslim communities and over the last twenty years has witnessed and even precipitated many occurrences of the process described. The rest of this essay describes the route to extremism in more detail, then demonstrates the more general friction points between the more easily identifiable sects by comparing each sect’s attitude to extremism, to newcomers, and to each other. Statistics are provided to show the relative significance of each sect. Cases that fit the analysis are explained in the context of each sect, and those that do not are fit are summarised afterwards. (It would be absurd to claim that this sect-rivalry model fits all cases, but knowing why some cases do not fit helps to understand the significant factors in those cases that do.)

[Please note that this work is still in preparation - I hope to release most of the above on to the website by the end of November 2008.]

2 The Process – Rivalry over Neophytes

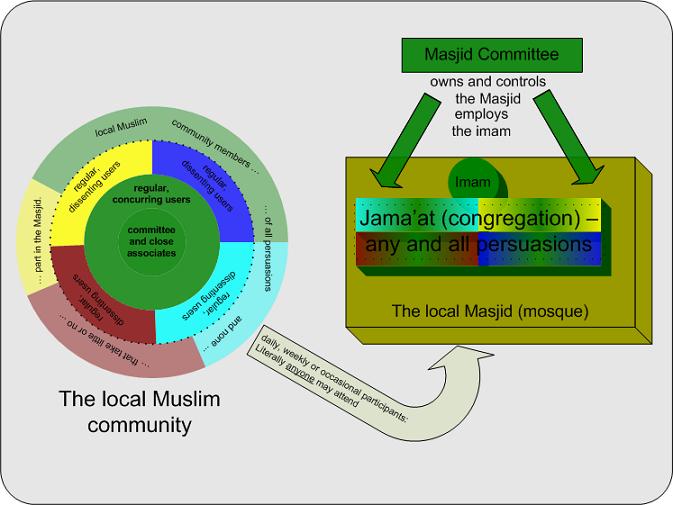

2.1 Neophytes and Masjid Sects

Men returning to the faith and converts to it alike, collectively neophytes, begin to attend the mosque, the masjid[2], regularly. Managerial control of the masjid is inevitably vested in one sect, invariably one of Deobandi, Bareilvi, Salafi, or Maudoodi-ist Jama’at Islami inclination. (These are the main Sunni factions, in declining order of occurrence[3].) Meanwhile adherents of the other mainstream sects are vying for an opportunity to influence the congregation in the masjid, and the management committee’s principle concern is to prevent them from doing so. Adherents of other marginalised opinions (radically moderate opinions, problematically radical ones and plenty of other ones too) also vie for influence, so the arrival of a keen neophyte ripe for cultivation is a big opportunity for each sect to expand its influence through winning the allegiance of the new enthusiast.

But the challenge for all of them lies in how to present their rival cases to the neophyte. No masjid will tolerate open debate[4]. Instead advocates of competing mainstream or marginal viewpoints take the neophyte aside out of public view to try to persuade him of the validity of their views. In the absence of the moderating influence of open, critical debate, the advocates’ arguments are framed in religious hyperbole and absolutist rhetoric[5]. Thus behind their backs, rivals are branded polytheists, grave-worshippers, traitors to Islam etc. rather than having their actual beliefs analysed carefully. Inevitably, rivals do the same, and do so with more fervour if the neophyte shows promise or is close to accepting a particular factional view. Although the reason why these activities take place discreetly is to avoid an open clash with the masjid incumbents or other rivals, such secretive discretion allows problematic groups and individuals to behave in exactly the same way as mainstream ones, clandestinely without interference.

Masjids are used by many, but controlled by few -

Masjids are used by many, but controlled by few -the few restrict activities of the many to just the basics: "Do as we do or pray-and-go."

One of the mainstream sects, particularly the Deobandis and Bareilvis (75-80% of all UK masjids are managed by either of these two), usually tend to have dominance of the management of the masjid. Few newcomers are content with these mainstream, older-generation factions, other than those whose parents are already steeped in these traditions and who are willing to maintain the family allegiance. These factions themselves have very little to offer the neophyte; for example they are far more likely to employ imams with minimal English language skills than are the other factions.[6] So it is almost inevitable that a neophyte, and especially a convert, will be drawn to a fringe group, whether from the mainstream and a minority locally, or from the more obscure fringes. Most masjids are also dominated by one particular ethnicity, yet have a patchwork of other ethnicities who use the masjid. Overlaid on religious factionalism, these increase the permutations of fringe factions, and therefore, the range of options open to the neophyte.

2.2 Neophytes and rival sects

As soon as the neophyte has been seen around with the adherents of one sect, rivals will seek discreet opportunities to persuade him of the faults of that sect, and promote their own. When the neophyte becomes an enthusiast for a sect, in his naïve enthusiasm he will often start open arguments about the rightness of that sect and the wrongness of the alternative, especially the dominant sect in the masjid. This gives him special value to the more disaffected sectarians, who otherwise remain quiescent because the dominant sect know who they are and will act quickly to suppress any efforts by them to raise their profile – the newcomer will neither have these inhibitions nor be dismissible by the incumbents, and will have genuine grievances over the almost invariable failure of the masjid to provide for his needs.

There is no progression here: Bareilvis and Deobandis/Tablighis are interchangeable at the start. All are interchangeable subsequently.

Although sects claim absolute differences between themselves and others, in general and in practical terms they differ only in emphasis on the priorities, e.g. Deobandis emphasise strict maintenance of the 5 times a day Salaah, though no other Muslim could deny this; whereas Salafis emphasise that all practice must be rooted in clear evidence from primary sources, which again no Muslim can deny. Jihad and action to defend Muslims from oppression are both bona fide Muslim practices that no sect can deny, and are highly topical, so that it is inevitable that the neophyte will either raise or be confronted with such issues, regardless of how moderate any group is that he becomes involved with. In the process either he or his adversary will take a position on militancy; simple logic ensures that one of them will take a more militant position than the other, even if both are well on the moderate side of the acceptability line. However as this process is repeated between the neophyte and other groups, the stakes are raised. The neophyte may side with the more militant line, or the more civil line, or might be a bystander while two groups squabble between themselves prompted by his interest in both. But his very presence energises the argument.

Over the course of several such exchanges, the neophyte may be drawn to different groups, but even if not, will certainly be approached by individuals with different views. (Note that the groups as they exist in local masjids may not have any formal existence, or even necessarily be aligned with any nameable entity, but are most often ad hoc peer groups of like-minded individuals.) Over time (and for many of those identified with terrorism and militant activity this can be just a few months), someone, either the neophyte or an adversary or a small group, persuades himself or themselves, into a position where action is essential to prove to himself or to others that this is not empty talk, and to show others the dedication and self-sacrifice of one who is true to the cause. If the issue is one of, say spiritual development, that person might become a dedicated Sufi. If the issue is one of religious rectification of the community, that person might become a dedicated Tablighi preacher. And if the issue is one of militancy, that person might join the jihad in Chechnya or might take a train to Kings Cross.

2.3 What the neophyte did next

A conscientious Muslim is obliged

to live in the world, but not of the world. For a good Muslim, life in this world has one

purpose alone, to gather deeds with which he will be rewarded in the next

world. The Messenger of Allah ![]() described the ‘great jihad’ as the struggle

against one’s base self, to surrender one’s self to the service of Allah. In his own time, the polytheists of Makkah

sought to exterminate the nascent Muslim community, and his companions not only

gave their lives to protect it, but vied with each other for the chance to die

defending it. That principle remains –

as Muslims, we should have no attachment to our worldly lives – if we sense our

worldly self holding us back, we should discard it by sacrificing it for Allah. Such views are not extremist, they are the

meat and bread of Islam.

described the ‘great jihad’ as the struggle

against one’s base self, to surrender one’s self to the service of Allah. In his own time, the polytheists of Makkah

sought to exterminate the nascent Muslim community, and his companions not only

gave their lives to protect it, but vied with each other for the chance to die

defending it. That principle remains –

as Muslims, we should have no attachment to our worldly lives – if we sense our

worldly self holding us back, we should discard it by sacrificing it for Allah. Such views are not extremist, they are the

meat and bread of Islam.

It ought to be obvious that the

nature of that worldly sacrifice is what is at issue – arguably polarised

between violent (self-) destruction and self-dedication to the common

good. Some knowledgeable readers may

defer to Sufi concepts and latch onto the notion, with reference to the

Messenger of Allah ![]() himself, that “the small jihad [the battle of

Tabuk against the Byzantines] is ended, the great jihad [against the base-self]

begins.” But for the neophyte, that

notion is self-evidently distorted: it is horribly clear to him that these

“minor” jihads are far from ended – Palestine, Iraq, Afghanistan, Chechnya,

Sudan, are all contemporary examples of Muslim lands invaded by kufr forces, and the long list of Muslim

countries with munafiq (traitor)

“anti-Islamic” governments in hock to kufr

powers, demonstrates to him that no succour will come from there – it is up to

him to show the way. In the words of the

Messenger

himself, that “the small jihad [the battle of

Tabuk against the Byzantines] is ended, the great jihad [against the base-self]

begins.” But for the neophyte, that

notion is self-evidently distorted: it is horribly clear to him that these

“minor” jihads are far from ended – Palestine, Iraq, Afghanistan, Chechnya,

Sudan, are all contemporary examples of Muslim lands invaded by kufr forces, and the long list of Muslim

countries with munafiq (traitor)

“anti-Islamic” governments in hock to kufr

powers, demonstrates to him that no succour will come from there – it is up to

him to show the way. In the words of the

Messenger ![]() , “Fight injustice with your hand, and if you

cannot, then with your words, and if you cannot, then with your heart, but this

[last] is the weakest of faith.”

, “Fight injustice with your hand, and if you

cannot, then with your words, and if you cannot, then with your heart, but this

[last] is the weakest of faith.”

Thuswise I have tried to set out the frame of mind of our determined neophyte, in terms that are not sensationalist, but that are common currency among conscientious Muslim youth. These views don’t require to be imbued through fiery lectures, or through programmed brainwashing in a retreat in exclusion from the rest of society. They don’t require sophisticated propaganda – indeed, not only is the propaganda mainly made up from western media content, but the counter-propaganda is mostly inept and shallow.

The covert options open for our newly militant, Muslim neophyte include (i) passive capacity building for some putative showdown, e.g. weapons training, (ii) passive support for active campaigns elsewhere, such as fund-raising and logistics, (iii) active paramilitary/guerrilla involvement in an organised and current insurgency, e.g. Iraq, Afghanistan, Chechnya etc. (iv) active terrorist activity in a key location, e.g. Israel or an Arab and oppressive anti-Islamic government, or (v) an act of terrorism in the west that is intended to precipitate a heightened state of crisis. Broken down in this sequence they represent increasing divergence from moral norms. It is worth noting that the first three did not cross any ‘normal’ moral or legal boundary until after 9/11. Small but significant numbers of Muslims from Britain participated in Kashmiri separatism since the 1960s. The British anti-fascist movement of the 1930s was popularly lauded for its contributions to the International Brigade in republican Spain while the British government took a critical view of them. In the 1980s British Muslims, including converts, fought in the Mujahideen against the Soviets in Afghanistan, indeed, on the same side as British and American special forces seconded to the same Mujahideen. So, not only is the neophyte’s religious mindset not exceptional, nor is his social, moral foundation either.

Following 9/11, much thinking around terrorism campaigns asserted very strongly that there exists a sophisticated network of middlemen performing various roles to talent-spot, groom, recruit, indoctrinate, train, support and supply cadres, and that this has to be organised in a top-down, directed and planned manner. Much of such thinking, at least in Britain, comes from experience of the IRA’s campaigns (I compare British Muslim militancy with Irish republicanism in Appendix 1). But I am arguing that on the contrary, no such sophisticated, external organisation needs to exist. It may very well exist, and I have two anecdotes that support this, but such a network is very risky in such an unreliable environment as UK Muslim society, would be very expensive to maintain and isn’t really needed when there are significant numbers who are prepared to self-recruit themselves. (The two anecdotes are of a Leicester man who I met in Jeddah who explained to me that he recruited people to fight in Bosnia – a home grown network of one, perhaps, and secondly, someone after 9/11 who told me he had been approached in the street by an Arab man and was explicitly asked if he was interested in jihad – he himself looked peculiarly like a typical Hijazi Arab though his ethnicity was very different, so my surmise is that the recruiter assumed he was on safe ground.)

There is no special need for the newly militant neophyte Muslim to seek out militant preachers to stimulate him. This may happen, but I hypothesise that is not a necessary part of the process since the strongest motivation comes from within the small group dynamic. I have no evidence that recent plots required such a motivation – it appears the Operation Crevice group did not do so, nor apparently did the Liquid Bomb plotters. Some of the July 21st 2005 bombers and some of the Chinese Restaurant conspirators met together and may have been inspired from within the UK, but there is no information regarding motivational preaching. Omar Bakri Muhammad spent time with a group in Derby before the Tel Aviv bombers set off – one of the pair was from the Derby group. Some of the July 21st 2005 bombers seem to have met with some of the July 7th 2005 bombers in Pakistan. While these points suggest an interconnected network, I contest that they did not interconnect and then turn militant – they were all militant groups on the fringe of local communities who then interconnected.

Pakistan is the natural destination for the would-be jihadi, not because Pakistan is especially militant, but because it is a very open, liberal and cosmopolitan society and because many people travel to and from there. There are half a million passenger movements between UK and Pakistan every year, which very crudely means that every person of Pakistani extraction in Britain travels there every eighteen months. Although British Pakistanis are mainly from particular parts of Punjab and Kashmir, travellers not settled in Britain include people from all over Pakistan. The extended family network means that British Pakistanis have a large number of scattered relatives and family friends to call upon in Pakistan, so travel and sustenance within the country are readily available. The would-be jihadi does not need any special arrangements to be made in advance in order to find people who can help him gather any resources he needs. Turning up in Pakistan in any town where he has a relative, the relative will vouch for him in the local community. The relative need have no knowledge of his true intentions.

A non-Pakistani, e.g. a convert, obviously may not have family connections, but very probably would have been befriended by a UK Pakistani family, and, travelling alone, he might possibly exploit that innocent friendship to make his first introductions in Pakistan. If that sounds a bit contrived, actually, from my own experience, conscientiously practising converts from the west have so much kudos in Muslim countries that they really don’t need any introductions, especially in a country like Pakistan where the religion is in the lifeblood of the country. The lack of language skills would not be a major handicap either – there are plenty of people around who can communicate adequately in sub-continental ‘English’. There are many, many thousands of masjids in Pakistan – these are the local communication hubs, rather like pubs in Britain. The newcomer will be very conspicuous and does not need to say or do much to draw the attention of a militant sympathiser in the crowd – perhaps a camouflage-styled fashion accessory or a borrowing from a cause, e.g. a Palestinian scarf, or something that deliberately jars with the status quo, e.g. an Arab-style shirt or affectation of an element of Salafi mode of prayer, are all things that will mark him out in a local masjid in Pakistan.[7] A little care and patience will see the emigrant neophyte quickly introduced to people that can help him on his way. Creativity might put the newcomer ‘timidly’ asking an elder in the masjid for advice on from whom he should steer clear, ‘being anxious not to get mixed up with any militants’. You can make up the rest.

If these suppositions seem at all contrived, I can cite much more bluntly disturbing examples in which an itinerant neophyte might quickly fall in with people who would help him towards mayhem. I met an American Muslim convert living in a very ordinary suburb of Karachi, in his practice radically at odds with the local Muslims but nevertheless quite comfortable, and an obvious person for a neophyte from Britain to approach. In Sharjah in the Emirates, I saw a small group of British Muslim expatriates who had gelled together there and may have been utterly innocent, but who were visibly uncomfortable with my presence and orthodox appearance – it was easy to imagine circumstances in which I could have found my own way into a budding extremist cell such as that group might have been. There are cases on record of young British men travelling in Pakistan with the intention of joining a militia, who have been less circumspect and happily accepted lifts from people who would take them to the nearest terrorist barracks, but who never reached their destination, instead returning home considerably poorer, the taxi driver’s friends considerably richer.

While most recent conspiracies have involved some members travelling abroad, the main purpose of such visits seems to have been consolidation rather than initiation – the individual or group have already made up their minds about what they will do, but need a chemistry or ballistics practical.

While I am sceptical that there is any effective role for recruiting agents to seek out potential recruits, cultivate them or hand them on to a terrorist network, I cannot deny that people have adopted such roles in a limited sense. My scepticism lies firstly in the relative ease with which one so minded may gain access to a extremist resources without the need for a go-between.

The second basis for my scepticism lies in recognising the constraint that a recruitment operator has to work within the narrow confines of local cliques of malcontents and gain their trust, where cliques defined by sect, ethnicity and, typically, youthful background, whereas the probability is that the recruiter shares none of these and therefore both fails to gain their trust and risks his own cover. Taking on that role in a peripatetic manner magnifies these difficulties.

| Masjid A | Bangladeshi Deobandi | Bangladeshi Sylheti, Asian professionals, Algerian and West African council employees, Morroccan local residents, Palestinian local residents, other North African casual workers |

| Masjid B | Bangladeshi Deobandi | Bangladeshi Sylheti, Asian professionals, Arab professionals, Asian students, Arab students, other North Africans |

| Masjid C | Bangladeshi Deobandi | Bangladeshi Sylheti, Gujerati Memon, Pakistani Punjabi Tablighis, Pakistani Kashmiri Salafis, Algerian, both Berber and Arab-speaking, other North Africans, Afro-Carib convert Salafis |

| Masjid D | Gujerati Deobandi | Gujerati Memon Tablighis and not Tablighis, Gujerati Surati, Pakistani Punjabi Tablighis and not Tablighis, Pakistani Kashmiri Salafis, Algerian, Egyptian, Afro-Carib convert Salafis, assorted hybrids...some converted, Somali and Sudani, Pakistani Muhajir young Salafis, Sri Lankan Tamils |

| Masjid E | Guyanese Deobandi | Pakistani Punjabi, Pakistani Kashmiri young Salafis, Afro-Carib convert Salafis, assorted hybrids...some converts |

| Masjid F | Pakistani Deobandi | Pakistani Punjabi Tablighis, Pakistani Punjabi Tablighis, Somali, Sudani, North African |

| Masjid G | Pakistani Deobandi | Kashmiri young salafis, Bangladeshi Sylheti |

| Masjid H | Pakistani Deobandi | Pakistani Punjabi, Pakistani Kashmiri, some English-speaking oddballs, local Hizb-ut-Tahrir, local Tablighis |

| Masjid I | Gujerati Bareilvi | Gujerati Kokni Bareilvis, Pakistani Punjabi Bareilvis |

Subgroups in a sample of masjids.

By way of illustration, this table shows a crude analysis of the make up of 9 masjids that I use regularly, in London, all located within an area 8 miles by 2 miles.

However my own thesis posits the existence of malcontents in the environs of any Muslim institution, and such a person, if minded, might well take on the role of militant recruiter as part of his attempt to demonstrate his credentials with my putative neophyte. I would hesitate to profile such a person, but a caricature of his adopted persona might be a dark-horse, mature figure (at least relative to his protégé) with accumulated resentments against the incumbent leadership of his locale. His attempt to “recruit” would essentially be opportunistic – he would get some satisfaction from potentially embarrassing the incumbent management if the protégé neophyte’s path traced back to the locality. He would not need much deep connection with any militant movement, merely some very superficial contact knowledge, e.g. knowledge of Pakistani militant groups’ political base, or, for a convert as recruiting agent, knowledge that an associate or former associate has already been involved in some form of overseas militancy so that the neophyte can be discreetly handed on. In short, the recruiter himself can take up his role only for a short time, and within the exact same rivalry dynamic I have already described.

2.4 How the Masjid management managed

Meanwhile, back in the masjid, all fringe activity and all rival mainstream activity that conflicts with the sectarian religious views of the incumbent management of the masjid, is at least obstructed, and is usually banned outright by the precarious management. Indeed many perfectly reasonable, non-sectarian events are often discouraged as well since their organisers may thereby gain kudos and support which challenges the incumbents’ hold. So meetings, activities and even one-to-one private discussions involving fringe groups, all take place out of public view, maybe in shadowy corners of the masjid, maybe elsewhere altogether. (Refer back to the table in Section 2.3 above, Subgroups in a sample of masjids, to see how doctrinal and ethnic sects and allegiances permeate all masjids. Whatever one might think of the preponderance of Deobandi managements in the sample, note that only sub-groups in these masjids have the same persuasion - the other groups all 'have to be kept in their place'.)

Thus all the expected tell-tale signs are absent – no-one except possibly a few intimates witness the few steps that take someone over the boundary into criminal violence, and even they may not be able to distinguish their peer’s genuine intent from their own empty bravado.

Obviously the Muslim community would have to be pretty naïve not to notice any heightened activity at all. Sadly some such communities do have the required degree of naïvity. Others lapse into complacency – a common response when a young man from a Pakistani family has become immersed in drugs or philandering, is to pack him off to relatives in Pakistan to dry out. I have no knowledge of such a sanction being applied to offspring digging into extremism, but not only is this inward-looking, homespun remedy disastrously ineffective with respect to drug abuse and probably so in nuptial abuse, if it were applied to extremism it would very much out of the chapatti pan into the firing line. Those local communities that do notice growing tension between sects in their catchment invariably respond by being even more obstructive of dissenters’ attempts to influence the congregation. Muhammad Siddique Khan was ‘banned’ from the Hardy Street masjid in Beeston – an impossible feat, but no doubt his activities were banned. Assad Sarwar of the airline liquid bomb plot was blocked from using High Wycombe’s Bareilvi masjids in the ways he wanted. The reason why these occurrences did not raise serious worries in their communities is that anyone else who dissented from the ruling faction would have been treated just the same, even if the dissenters were in favour of benign change, or had no ‘political’ motivation at all.

It is no coincidence, indeed it is an empirical fact, that most terrorism activity involving UK Muslims includes at least one convert to Islam, and all of them involve mostly neophytes, precisely as this analysis implies they will. Furthermore none of them involve mainstream Muslim bodies in any supporting role, but, and this is crucial, almost all involve people who have been obstructed from participation in the mainstream. Mainstream ‘lockdown’ of masjids against mainstream or fringe rivals, mainstream failure to understand militancy, mainstream blocking out of militant-minded youth, mainstream failure to cater for neophytes from its own community and especially for converts, are all different shades of the same problem, that mainstream Muslim sectarianism creates the conditions that allows militancy to thrive in the hinterland; and sectarian rivalry, both mainstream and fringe, create the conditions that make criminally militant activity, terrorism, inevitable for some.

3. Recipe for Isolating Extremism in 11 Steps

3.1 Undoing Sectarianism (Steps 1 to 5)

Mainstream Muslim sectarianism may cause extremism to flourish, but the mainstream does not do so intentionally or wittingly: it is not blameworthy; it causes extremism to flourish by shutting it out and driving it underground, unchecked and unseen. The mainstream does so to protect itself from extremist influence. Shutting unwanted factions out is the only security measure that mosques have.

Countering sectarianism is vital to marginalise extremists, is in no way simple, and has to be successful – the wrong approach will have the opposite effect. Countering sectarianism has nothing to do with the 14 centuries’ old, chestnut of Muslim unity; it has to do with tolerance, mutual respect, honesty and informed discussion between Muslim factions. These are values that Muslims seek in engagement with the rest of society, so it is both apt that we should seek them here and significant that they are hard to find.

The right approach to overcoming sectarianism must be organic, at a local level.

Thirdly, and most problematic, there is no natural authoritative body to turn to. Most UK Muslim organisations are autonomous anyway, even within factions. There is no overarching religious authority, especially in Sunni Islam (and Shi’a only constitute about 3 to 4% of UK Muslims). In the past, disputes over control of masjid premises have been handled through ad hoc mediation. A battle for control of a major (Bareilvi) masjid, Upper Park Road in Manchester, was mediated through inviting a senior local police officer to adjudicate. One in Luton, Westbourne Road (also Bareilvi) was determined in the High Court, and one in Southend was determined with the assistance of the Electoral Reform Society. These all occurred in the 1980s, and since then the growth of wealth within the Muslim community has meant schisms on this scale are usually resolved through breaking away to alternative premises.

Clearly, given the problem as I have described it, and the objective of changing the environment so as to prevent the exploitation of marginalised schisms by extremists, further fragmentation is the opposite of what is needed. Local masjid communities will need to find appropriate people to form an adjudication body to resolve what will usually appear to be very trivial disputes over, perhaps, conflicting timing of rival events, or matters of obscure religious significance, and in spite of their apparent triviality or obscurity, may need at first to bring in people who are both thoroughly independent and unquestionably authoritative within the community, quite probably non-Muslims, for example. (Local Muslim politicians, councillors or other “community leaders” most emphatically will not meet these requirements – Muslim involvement in mainstream politics has thus far been highly obstructive and factional – examples are cited in the following sections.)

3.2 Securing the Masjid (Steps 6 to 8)

For all their problems, the current arrangements that govern almost all masjids are quite stable and secure, if only for the preservation of the incumbent managements in post. That fact itself will cause most managements to be wary of change. Most management committees will be reluctant to recognise the problems of marginalisation in the terms I have described, though many users will be quick to endorse my critique. At best, the response will be the complacent aphorism, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it!” The fact is, it is “broke”, but not in ways that the old guard recognise. Indeed the recently published MINAB guidelines[8] do little more than encourage masjid managements to be nice to people and to respect the law. Most current managements would claim already that they comply with the MINAB guidelines (actually most, I suspect, are oblivious of them), and might own up to such caveats on ‘niceness’ as they require to maintain security … precisely to protect their controlling position from others who would change the direction of the masjid.

The underlying problem is that three different things have become intertwined that all presume that the status quo is desirable –

- the entrenchment of well-established factions (who treat sectarianism as a norm and are blind to the disastrous consequences),

- preservation of physical security, i.e. reducing the threat of confrontation and its consequences,

- and managerial stability and accountability, to be addressed now.

- sectarianism needs to be rationalised and discussed intellectually instead of emotively - Steps 1 to 5 above begin this process;

- physical security requires an entirely new approach to the status quo – I propose a “church warden” model which I explain further on, which co-opts regular users of the masjid, or any community resource, into a trusted partnership, ending the mutual suspicion that currently pervades community relations;

- and managerial stability must be abstracted from these other two to become dependent on transparency instead of obscurity – I cite an example of a robust model currently in use in one UK masjid, that may achieve this.

Step 6 Recognising the Problems

I will firstly describe some reasonable difficulties and then describe one existing stable model that may work appropriately once security and sectarianism have been teased out. The difficulties lie in defining the franchise, suffrage and membership of masjids, and in agreeing or accepting the purpose of the masjid.

It is impossible to define the suffrage of a masjid uniformly satisfactorily – is it all the Muslims

- living in a geographical area;

- living and working in an area;

- those who have subscribed a minimum membership amount;

- those who have donated most to pay for the property;

- those who use the facilities daily, or weekly, …, or at all;

- those who sympathise with the sect of the incumbent management or the founders;

- those from the same ethnicity as the founders, or with one parent, or one grandparent from that region, or that country, province, or town,

or some combination of these?

None of the possibilities is entirely satisfactory; nevertheless most masjids’ constitutions (written or unwritten) have conformed to some version of any one of these. Even the most obvious one, a membership roll, is subject to blatant abuse. For example in 2007 a prominent south London Islamic Centre raised its membership fee from a token £25 per annum to £125 per annum and introduced a one-off joining fee of £250. Just prior to this change, one imam had been dismissed by the management committee, and a body of masjid users, few of whom were ‘members’, were preparing to use the forthcoming AGM to protest about the dismissal. Around the same time, just a mile away, another long-established masjid repeated precisely the same formula, at a time when a substantial number of Somalis had become users of the masjid, none of whom were ‘members’ of the Pakistani-dominated management organisation. I do not know the reason for the changes in membership criteria; both masjids are relatively wealthy, but in each case the protesters and the Somalis respectively, believed themselves to have been deliberately shut out of influencing management.

As for the purpose of a masjid, again while one might suppose this is self-evidently a place of worship akin to a church, synagogue, gurudwara, ashram etc., reflection on the origins of masjids in Britain show that this is a little more complex, especially in the context of making masjid management more accountable and transparent. Most of the 1960s wave of Asian immigration was of working men attracted by employment offers in a country with no halaal food, no family life, and no Friday prayers. Those who came were, most likely, the least religious of Indian and Pakistani Muslims. Masjids slowly became established as the slightly more religious started to make arrangements for Friday Jumu’ah, and for mother-culture education of the children that came later. Many of them were set up as Pakistani / Bangladeshi / Indian Welfare Associations, with strong emphasis on mother-tongue teaching and events. In a certain sense they are the poor cousins of the colonial country clubs, Irish clubs, Helenic clubs and Italian clubs that pepper the old European colonies. ( Note how the European minorities within coloniser minorities became parodies of themselves.) Other masjids, especially in recent times, are completely the opposite – they are set up explicitly to propagate the doctrines of a given religious sect, usually as conscious rivals to nearby and dominating ‘general’ masjids (the latter having become sectarian through inertia), or as zawiyas or khanquas, the dedicated teaching centres of Sufi shaykhs. Others are set up principally as multi-purpose community centres, albeit explicitly for the Muslim community, or as schools or Islamic colleges which, because of their significant or exclusively Muslim clientele, provide masjid facilities. Others again are communal spaces, e.g. nominally multi-faith prayer rooms, often actually only used by Muslims. All of these sorts of organisation have a legitimate right to claim some exclusive, sectarian control for themselves. Nevertheless they are just as likely to be used as masjid venues for many people who have no other empathy with the aims of controlling organisation, so are just as likely to cultivate rival sectarian claims among marginalised users, and hence potentially cultivate extremism. It is therefore incumbent upon any organisation that claims a special, exclusive status, also to make similar arrangements for access to its resources by other sects and to moderate its references to other sects, at least in the milieu of its masjid facilities. There is a real danger that so many bodies will claim this kind of privilege that the overall situation will not change. It will then be up to the mass of masjid users to press such bodies for change.

Step 7 Constitutional Stability

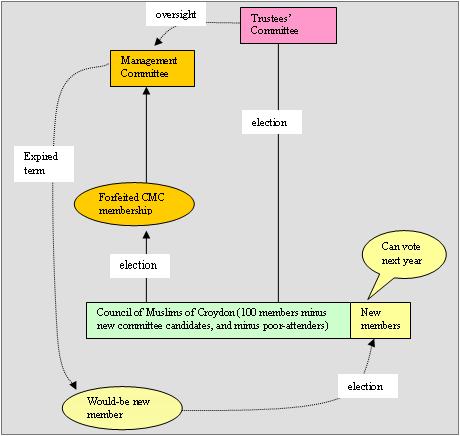

I do not propose any particular form of constitutional form as ‘right’ for masjids, but one example is worth examining because of its ability to allow change but only over a long period and by very dedicated people, with the change requiring the support of a large body of committed regulars. Croydon Masjid has a multi-tiered management structure. It is a large masjid in South London and there are very few other masjids nearby. It has a management committee with executive responsibilities, elected by an electoral college of members, and a trustees committee with oversight responsibilities, elected in the same way. Its constitution does nothing to prevent sectarianism per se, but it does provide a framework which is transparent and very stable.

The clever thing is the formation of the electoral college. This consists of never more than 100 people, the Council of Muslims of Croydon (CMC), which meets twice-yearly. Committees are elected annually, by and from among members of the CMC, who forfeit their membership of the CMC to take up an executive post on the management committee. The new committee members may not vote in the CMC, and immediately after the committee elections, the CMC votes among itself on new candidates for the depleted CMC, i.e. to fill the positions vacated by newly elected committee members, as well as positions vacated from within the CMC by those who have failed to attend 3 out of 4 of the previous CMC meetings. Thus the electoral college cannot be abused through short-term membership stuffing because only a few positions fall vacant each year and because new members have to wait one year before influencing the vote for the executive, as well as attend a reasonable number of meetings. Furthermore, new candidates for the CMC electoral college are themselves voted in, by a ballot of the CMC after presenting their cases to the whole CMC. Although the issue of a proper suffrage is unresolved, firstly it is not subject to the arbitrary decisions of an incumbent membership secretary but to the CMC, and secondly it is not subject to a discriminatory membership fee. Thirdly, newly elected CMC members’ commitments are tested through their subsequent attendance at CMC meetings, so even if suffrage includes ‘inappropriate’ people, they have to make an appropriate commitment and have to wait one year before wielding any influence. The rate of change is typically 10 to 15 members per year, so it would take several years of sustained effort for a group to make any significant change of direction of the masjid, through a process that is equally accessible to rival groups.

Schematic of Croydon Masjid’s Constitution’s Electoral College

This structure did allow one or two members of Hizb-ut-Tahrir to enter the masjid committee for a short time in 2006. I contend that this was a good thing, although a sensationalist joint edition of BBC’s Newsnight and Radio 4’s File on Four programme[9] tried to imply a connection between these Hizb-ut-Tahrir-supporting committee members, altercations outside Croydon Masjid, and a purportedly militant gang involved in a few acts of petty crime, through editorial juxtaposition of unrelated people and events. Hizb-ut-Tahrir is discussed in more depth later on, but it is important not only to note the false impressions created by that programme, but also that Hizb-ut-Tahrir in Britain have never so far made any attempt to gain a controlling interest in any masjid – their modus operandi is always to operate on the margins – literally so as they stand on the marginal pavements outside masjids distributing their dense single page leaflets that are devoid of almost any whitespace.

Step 8 Physical Security

Before 11th September 2001, I learnt of more than half a dozen physical fights between masjid users in Britain, all of them involving people of rival Sunni religious sects, all taking place near masjids where the disputes were centred. In Zimbabwe I learnt of an incident inside a masjid between a Bareilvi and a Deobandi, both Gujerati, in which a knife was drawn, and a very similar incident (a Bareilvi and a Deobandi, both Gujerati) in South Africa in which a man was stabbed to death in a masjid. At the time, no other factions had any significant presence in these countries. Since 2001 I have not heard of any more incidents like this, and the disputes over control of masjid committees have become far fewer as sufficient wealth has accumulated in the community for dissenting groups to break-away and find new premises instead. Nevertheless, anyone who can assert control over the imam’s prayer mat, usually by being there when the imam is away, has enormous opportunity for imposing his own interpretation of Islamic practice on the congregation. Abu Hamza al-Masri, the former dishwasher, epitomised this when he offered to lead the salaah in Finsbury Park masjid after the management had dismissed two consecutive employed and qualified imams over trivial issues (I knew both of them). His Arabic language (and his English language too), his brazenness and clear support for him from the congregation (consisting of a handful of forceful young men), made his claim to the imam’s mussalaah (prayer mat) irresistible. Fear of anything similar to that, whether from obvious militant extremists or from obviously animated ultra-liberal ‘extremists’, convulses incumbent management committees into urgent measures to make sure the imam is there, is ‘their’ man, and only trusted elders get to have any say in appointing him or permitting events such as visiting speakers.

This real fear of usurpation of the imam’s position and consequent loss of control of the masjid, is the main obstacle to opening up the masjid and Muslim community organisations to the demands of the youth. Solutions to this problem will vary considerably depending on local circumstances and local masjids’ resources. Confrontational situations may become disastrous for the stability of the masjid without ever escalating to the point where the police could be involved. Yet it may be appropriate to exploit improved police-community relations to allow police to have greater visibility as benign, routine visitors to the masjid. On the one hand Margate’s main masjid has a non-Muslim police officer who attends every Friday salaah, standing at the back and holding an informal ‘surgery’ after the salaah for anyone who wishes to raise an issue. On the other hand I have met police officers who wouldn’t dare enter a masjid without having a full officer safety review first and a backup team on hand. (I have wondered if perhaps their reluctance stems from being embarrassed to reveal the holes in their socks.) Clearly there is a role for Muslim police officers here, yet they are very few. There is also a role for encouraging responsible Muslims that use the masjid to become involved as special constables. I have discussed how this may be developed in Appendix 2.

Even if these approaches were adopted, there is still a huge gap of understanding of the issues by the authorities at any level, and of recognising an appropriate level of intervention. Most masjids would in fact be desperately keen to keep these kinds of problems very close to themselves, due (i) to the difficulty of understanding the issues, (ii) due to either suspicion of police motives or that their involvement would alienate youth, and (iii) due to the nauseously hostile and ignorant nature of media reporting of any such incidents. Disregarding all the above, at face value problems such as a dispute over who should lead the salaah can hardly be described as a matter for the police. What is missing is someone of impartial authority in the masjid. Appendix 2 describes such a person as akin to a Church Warden. That person would have a close and positive relationship with local police and the local authority without being their stooge, which would give him implied access to authority. He would be routinely in the masjid for most of the regular salaah, and he would not normally take any active role – not as deputy for the imam nor as a committee member. And a generally accessible local complaints procedure would need to be in place to ensure he did not abuse his position.

3.3 Safe Paths for Neophytes and Dissenters (Steps 9 to 11 and beyond)

Step 9 Give local figures knowledge of issues and factions

Even though by this stage we aim to have achieved a level-headed attitude towards other factions, one of the key difficulties in tackling extremism is the absence of accurate knowledge of the issues. There is a large amount of false information from Muslim sources briefing against rival mainstream factions, that has to be unpicked, above and beyond the simplistic arguments that should already have been surmounted. There is a lot of historical, political and geographical context surrounding all of the emotive issues that feed militants’ simplistic claims concerning contemporary issues. And there is a large amount of knowledge to accumulate about groups that local militants might claim to represent or might eulogise, this knowledge consisting not only of the same kind of contextual material, but also of sustainable religiously-founded arguments against such groups. Such information comes from highly specialised religious and academic sources, is unlikely to be available locally, and probably needs to be taught in dedicated forums with provision of high quality supporting material. Currently the only material that addresses this area is either platitudinous or undermined by its own sectarian starting point. The people who need this information are imams and other religious figures (who are, to an outsider, amazingly ignorant of these matters), but also other local figures who are looked upon for advice, e.g. conscientious worshippers that are frequently in the masjid, local ’amirs of Tablighi Jama’at, leaders of Sufi gatherings, individuals running study circles or bookstalls, and many others depending on local circumstances.

Clearly a lot of thought has to be put into preparation, consolidation and dissemination of this sort of material, and although it is Step 9 in terms of the point at which it becomes required input, its preparation could and should be started immediately, and would require significant central funding.. The worry about starting immediately, out of context of this anti-sectarianism drive, is that problem issues and problem groups will be covered too superficially until a clear local need is perceived, and that the preparation work itself will be mired in the sectarian complacency that sticks to all current activity – the feeling that extremism is someone else’s problem because ‘our’ sect has kept it out from ‘our territory’.

It would be easy for anyone that has not been directly involved in dialogue with would-be militants, to under-estimate the difficulties involved in preparation of counter-militant material, especially given the platitudinous responses that the Muslim establishment has thus far produced. In fact such material may be counter-militant but is unlikely to be counter-radical, because the issues aired by radicals include deep and real grievances. Militant arguments, especially those couched in religious terms, are sophisticated and highly evolved. Counter arguments are very easily interpreted as flaccid or collaborationist. And having once documented them, are readily available for counter-counter arguments.

Step 10 Meet the needs of neophytes - impartially

My entire argument is centred on the way in which neophytes are drawn in to conscientious practice of Islam. I do not propose here to define the right way this should be managed, but masjids must put in place an agreed procedure that addresses all the issues that make neophytes vulnerable to exploitation, and must do so in a way that is transparently even-handed. Neophytes’ needs will vary, but include

- Most particularly, accurate and impartial definitions of the sectarian options confronting him. Having these documented publicly, in line with Step 3, means that any wilful misrepresentation will be challengeable, in line with Step 5.

- Tuition in appropriate Islamic knowledge. This must include the religious foundations of orthodoxy as well as those of Salafi-ist methods. This is because dreadfully poor versions of the former lead many neophytes and most converts towards the latter in derision of the orthodox establishment. And it is because Salafi-ist methods are frequently hijacked by militants to provide pseudo-intellectual support for their positions.

- Tuition in Arabic language. This is one of the areas where the neophyte is most vulnerable to factional subversion because almost anyone with a bit of determination can better the offering of traditional Qur’an learning by rote, that being the only option available in most masjid establishments, in a room full of primary-school children. And among the ‘almost anyone’ will certainly be those with a more sinister motive, if they are present.

- Proper and responsible attention to welfare needs. Most neophytes whether converts or born-Muslims, return to conscientious faith from a position of stability, so welfare needs are usually not an issue. Indeed one of the motivators for born-Muslims in their twenties, is to recapture some of their social responsibilities at a point when they intend to settle down. However I have been directly involved in several cases of converts who had major welfare problems that were badly mishandled by well-meaning people in masjids they attended. Three involved highly impressionable men with schizophrenic maladies who needed professional medical help, and in two of those cases Muslim helpers instead organised utterly inappropriate marriages for them, with profoundly negative consequences.

Step 11 Move from factional tolerance to mutuality

Progress up to this stage should have achieved a safe and confident management structure, open and informed discussion of factional and controversial issues, respectful references to differing factions, and use of the masjid by parties that are not supported by the masjid management. Infrequent users of the masjid would by now have these values instilled in them through the examples of the key figures and the frequent users; there should be displays of factional definitions against which their local advocates can be measures, and protocols for access to masjid resources, making complaints and induction of newcomers.

It is now necessary to build this up into a community-wide network. The Home Office’s Preventing Extremism Together report[10] made much of supposed ‘beacon mosques’ – the more well-endowed showcase masjids in major Muslim population centres. I do not believe that concept is very helpful. In many areas, the smaller, poorer, satellite masjids exist precisely because they have antipathy to the big masjid – they are rivals, divided through religious or ethnic sectarianism or over management rifts. Promoting the big masjid as a ‘beacon’ would exacerbate the rifts.

Instead, a more delicate process of integration will be required. Different factional interests within a masjid could be brought together in the atmosphere of tolerance that would have been created if they got this far, brought together to organise jointly events associated with special calendar dates, and in a way that works constructively on their differences, not in a way that papers over them. Masjids often have events that involve a communal meal – minorities, especially ethnic ones, could be invited to provide their own ethnically defined catering at a majority event, e.g. the small number of North African families could provide their cuisine at a 10th Muharram event. Or minority ethnic groups who have a particular issue might be given an opportunity to air the issues by dedicating an evening to a programme in which they take the lead. Similarly in reverse, events could be conjured up in which a dominant faction, e.g. Bangladeshis (who usually manage their own masjids in a very exclusive way) might invite all the non-Banglas to be involved in something concerning Bangladesh that is explicitly aimed at non-Bangladeshis. These examples are all highly contrived, but deliberately so – they must be seen more for their role in breaking down local barriers than for their nominal purpose. As I have described them they are also the precursor to involvement of other neighbouring masjids: it is highly likely that minorities in one masjid will need to call on help from their peers further away who habituate other masjids.

Such events lead on to co-operation between neighbouring masjids. Besides building the necessary bridges required to propagate the steps I have elaborated so far, neighbouring masjids, especially those who have hitherto snubbed each other on sectarian grounds, must consolidate their programmes in the local community. This can be aided if rather formal visits are made between masjids – the bulk of the regular users of one masjid turn up to another masjid as invited guests for some event. Since etiquette demands a return visit, including a third masjid at the event will maintain the momentum.

Beyond Step 11

If these recommendations start to sound trite, it is worth reminding ourselves of the objective. Indigenous extremism arises from individuals or ad hoc groups operate unchecked in the margins of the masjid because sectarian and autonomous managements are unable to handle any kind of dissent except by shutting expression of it out. Dissent is emotive and threatens their control – the proposals I have made seek to intellectualise and normalise dissent, to bring it in from the cold, and to give incumbent management the means to become more tolerant of it without undermining their security. This then isolates malicious, extremist dissenters since they must remain in the margins.

One might compare my suggestions with the Mosques and Imams National Advisory Board, MINAB. Their recommendations are included as Appendix 3. MINAB is a collection of enthusiasts from four umbrella bodies, the Al Khoei Foundation (Shi’a), the British Muslim Forum (Bareilvi), the Muslim Association of Britain (Levantine Arab), and the Muslim Council of Britain (a mixture). Only about 20% of the UK’s 1500 or so masjids affiliate with these organisations and none is under any obligation to follow their guidance, indeed all are jealous of their autonomy. MINAB’s recommendations are perfectly reasonable in encouraging good governance, inclusivity and engagement, but completely ignore factionalism and the need for masjid security, and provide no means for achieving the stated goals.

It would be vain of me to try to map out any further steps beyond these eleven. The vital points are that there is a lot of interconnectedness, that worthy actions without preparation of the ground, will fail, and some are highly likely to inflame the situation, and that the only actions that will make a difference are local ones that grow organically. A lot of the preparatory work involves ‘capacity building’ and this term really does mean something. I could provide a long shopping list of precise skills and materials that have to be cultivated, but again, local circumstances will determine these. My Shrivenham Paper, “Problems and Practical Solutions to Tackle Extremism”,[11] did enumerate around fifty specific things to do. This document puts some of them into a plan. Currently, local authorities are stymied by a lack of funds and controlled access to the Muslim community through ‘gatekeepers’ with status and reputation to protect, often the very people who unwittingly are the butt of frustrated young radicals’ issues. So this is a good point to look closely at what actually are the sectarian tensions and drivers that I claim are the dynamics of extremism in Britain.

Large parts of the rest of this document are nearing completion in October 2008 and will be published here shortly.

[1] Most of the more emotive material is made of the same newsreel clips that are aired on TV – their very familiarity makes them more powerful when placed in a “jihadi” context, because by being public news material and seen by all, they reinforce, in the would-be militant, the sense of apathy among those around him from which he must break out.

[2]The word mosque comes from the French word ‘mosqué’ which is a crude rendering of the Egyptian dialect masgid derived from the original Arabic masjid, meaning a place for prostration. Masjid is the correct term, and the English word ‘mosque’, while widely used, has no valid meaning. Purists will note my failure to render the plural as masaajid, just as I have followed the convention of ‘Muslims’ in preference to using muslimeen.

[3] There are approximately 1,600 masjids in the UK. About 55% are managed by Deobandi sympathisers, about 25 to 30% by Bareilvi sympathisers, 3% Jama’at Islami supporters, 4% Salafi / Ahl-e-Hadith, 4% Shi’a and around 5% other. Note that the congregation and local Muslim community will include a heterodox mixture from these – few masjids are explicitly or exclusively denominational among their congregations.

[4] A simple proposition will underline this, namely: No Muslim can tell you that he or she has ever witnessed two authoritative Muslim religious scholars from different factions taking part in a public debate on the same platform, over their respective factional differences, anywhere in the world.

[5] Takfir, the pronouncement of being a kafir, a non-believer (lit. an ungrateful) is not the exclusive preserve of extremists. Many members of most groups with strongly held views, including Bareilvis especially, make the claim of takfir against their opponents. This author would do the same in relation to the Ahmadiyya or Qadianis, for example, as they would in turn to all non-Ahmadiyya. Obviously most such verbal pronouncements do not extend as far as encouraging the unwanted sect’s extermination. See footnote 21. [To be added soon]

[6] The reason why there are so many imams with little or no English is primarily economic. The vast majority of masjids are run on a shoestring budget in run-down properties, financed by the Friday collection that averages a pound a head. The imam must be there (see the section ‘Imams - The Role of the Imam in Islam in Britain’ below) to lead the five-times daily salaah – if he is not, someone else is obliged to lead the salaah, often someone the management would prefer not to. The imam is therefore essential to keep the masjid from falling into rivals’ hands – his English is a secondary priority. Few people raised in Britain would accept the pitiful employment conditions of most imams. (Contrary to the belief of many critical non-Muslim commentators, only a tiny handful of masjids have ever received any funding from overseas, and then only for construction costs. Generally the converse is true - many Islamic institutions overseas come cap-in-hand to British Muslims for assistance.)

[7] Only the stupid would take my examples here as ‘indicators’ of potential extremists – the point of these examples is that they are quite banal yet in the right context the most banal sign can initiate the required conversation. Unfortunately, when faced with a poorly understood community, CT practitioners often suspend common sense for this sort of stupidity. I am optimistic that the readers who have made it this far are among the wise.

[8] “Good Practice Guide For Mosques And Imams In Britain” Published by Mosques and Imams National Advisory Body, 2007, included in Appendix 3.

[9] “Investigating Hizb-ut-Tahrir”, aired on 14th November 2006, reference http://www.bbc.co.uk/go/homepage/int/news/-/mediaselector/check/nolavconsole/ukfs_news/hi?redirect=fs.stm&nbram=1&bbram=1&nbwm=1&bbwm=1&news=1&nol_storyid=6148560 Having been a committee member of Croydon Mosque myself in the past, I was able to verify that Croydon Mosque had no particular complaint and that the programmes’ implied connections were baseless. The Newsnight programme also conflated the peaceful Hizb-ut-Tahrir (HT) with the militant Al-Muhajiroun without explaining that the latter was a different entity which broke away from HT in the 1990s.

[10] ‘Preventing Extremism – Working Together’ Working Groups August – October 2005, published Home Office, November 2005. http://www.communities.gov.uk/documents/communities/pdf/152164.pdf

[11] Mehmood Naqshbandi, Problems and Practical Solutions to Tackle Extremism; and Muslim Youth and Community Issues, Shrivenham Paper Number 1 (Defence Academy of the UK, Aug 2006).